Modest and elegant

No serious believer will deny that in our time sexual perversions are propagated and modesty and chastity ridiculed. Today’s political correctness is siding with those who attack traditional family life, religion, and the divine laws of nature and revelation.

This counter-culture of perversion has invaded traditional Christianity on a massive scale since the end of the Second World War. It started with the mistaken emancipation of women and feminism and is now involved in the diabolical attempts to destroy all traditinal morality by the LBGTQ and Gender Ideology movements.

When in the late 50s and early 60s of the XXth century emancipated women began to dress like men, only a few prophetic voices foresaw what was coming. One of these voices was the Roman Cardinal Siri’s. [1] In a pastoral letter entitled: Notification Concerning Men’s Dress Worn By Women, dated June 12, 1960, this staunchly conservative Catholic prelate dealt with the roots of the problem in an excellent psychological and social analysis based on the principles of natural law. [2]

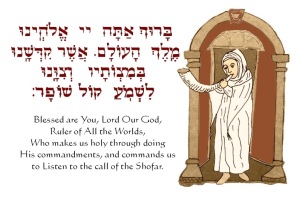

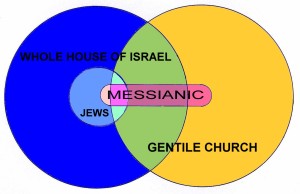

We decided to republish this Notification for our readers. It highlights aspects of sexual morality which are often overlooked by believers of evangelical upbringing, but which are quite familiar to traditional Catholics and religious Jews. Messianics will discover that Siri’s analysis provides a general clarifying background to many Torah injunctions and prohibitions on the domain of the social interacting of the sexes as well as on traditional Jewish fence laws.

I expect that Siri’s letter, given here below, will surprise many readers for its actuality, relevance and depth of vision.

Notification Concerning Men’s Dress Worn By Women

By Giuseppe Cardinal Siri

Genoa,

June 12, 1960

To the Reverend Clergy,

To all Teaching sisters,

To the beloved sons of Catholic Action,

To Educators intending truly to follow Christian Doctrine.

I

The first signs of our late arriving spring indicate that there is this year a certain increase in the use of men’s dress by girls and women, even family mothers. Up until 1959, in Genoa, such dress usually meant the person was a tourist, but now it seems to be a significant number of girls and women from Genoa itself who are choosing at least on pleasure trips to wear men’s dress (men’s trousers).

The extension of this behavior obliges us to take serious thought, and we ask those to whom this Notification is addressed to kindly lend to the problem all the attention it deserves from anyone aware of being in any way responsible before God.

We seek above all to give a balanced moral judgment upon the wearing of men’s dress by women. In fact Our thoughts can only bear upon the moral question.

Firstly, when it comes to covering of the female body, the wearing of men’s trousers by women cannot be said to constitute as such a grave offense against modesty, because trousers certainly cover more of woman’s body than do modern women’s skirts.

Secondly, however, clothes to be modest need not only to cover the body but also not to cling too closely to the body. Now it is true that much feminine clothing today clings closer than do some trousers, but trousers can be made to cling closer, in fact generally they do, so the tight fit of such clothing gives us not less grounds for concern than does exposure of the body. So the immodesty of men’s trousers on women is an aspect of the problem which is not to be left out of an over-all judgment upon them, even if it is not to be artificially exaggerated either.

II

However, it is a different aspect of women’s wearing of men’s trousers which seems to us the gravest.

The wearing of men’s dress by women affects firstly the woman herself, by changing the feminine psychology proper to women; secondly it affects the woman as wife of her husband, by tending to vitiate relationships between the sexes; thirdly it affects the woman as mother of her children by harming her dignity in her children’s eyes. Each of these points is to be carefully considered in turn: —

A. Male dress changes the psychology of woman.

In truth, the motive impelling women to wear men’s dress is always that of imitating, nay, of competing with, the man who is considered stronger, less tied down, more independent. This motivation shows clearly that male dress is the visible aid to bringing about a mental attitude of being “like a man.” Secondly, ever since men have been men, the clothing a person wears, demands, imposes and modifies that person’s gestures, attitudes and behavior, such that from merely being worn outside, clothing comes to impose a particular frame of mind inside.

Then let us add that woman wearing man’s dress always more or less indicates her reacting to her femininity as though it is inferiority when in fact it is only diversity. The perversion of her psychology is clear to be seen.

These reasons, summing up many more, are enough to warn us how wrongly women are made to think by the wearing of men’s dress.

B. Male dress tends to vitiate relationships between women and men.

In truth when relationships between the two sexes unfold with the coming of age, an instinct of mutual attraction is predominant. The essential basis of this attraction is a diversity between the two sexes which is made possible only by their complementing or completing one another. If then this “diversity” becomes less obvious because one of its major external signs is eliminated and because the normal psychological structure is weakened, what results is the alteration of a fundamental factor in the relationship.

The problem goes further still. Mutual attraction between the sexes is preceded both naturally, and in order of time, by that sense of shame which holds the rising instincts in check, imposes respect upon them, and tends to lift to a higher level of mutual esteem and healthy fear everything that those instincts would push onwards to uncontrolled acts. To change that clothing which by its diversity reveals and upholds nature’s limits and defense-works, is to flatten out the distinctions and to help pull down the vital defense-works of the sense of shame.

It is at least to hinder that sense. And when the sense of shame is hindered from putting on the brakes, then relationships between man and women sink degradingly down to pure sensuality, devoid of all mutual respect or esteem.

Experience is there to tell us that when woman is de-feminised, then defenses are undermined and weakness increases.

C. Male dress harms the dignity of the mother in her children’s eyes.

All children have an instinct for the sense of dignity and decorum of their mother. Analysis of the first inner crisis of children when they awaken to life around them even before they enter upon adolescence, shows how much the sense of their mother counts. Children are as sensitive as can be on this point. Adults have usually left all that behind them and think no more on it. But we would do well to recall to mind the severe demands that children instinctively make of their own mother, and the deep and even terrible reactions roused in them by observation of their mother’s misbehavior. Many lines of later life are here traced out — and not for good — in these early inner dramas of infancy and childhood.

The child may not know the definition of exposure, frivolity or infidelity, but he possesses an instinctive sixth sense to recognize them when they occur, to suffer from them, and be bitterly wounded by them in his soul.

III

Let us think seriously on the import of everything said so far, even if woman’s appearing in man’s dress does not immediately give rise to all the upset caused by grave immodesty.

The changing of feminine psychology does fundamental and, in the long run, irreparable damage to the family, to conjugal fidelity, to human affections and to human society. True, the effects of wearing unsuitable dress are not all to be seen within a short time. But one must think of what is being slowly and insidiously worn down, torn apart, perverted.

Is any satisfying reciprocity between husband and wife imaginable, if feminine psychology be changed? Or is any true education of children imaginable, which is so delicate in its procedure, so woven of imponderable factors in which the mother’s intuition and instinct play the decisive part in those tender years? What will these women be able to give their children when they will so long have worn trousers that their self-esteem goes more by their competing with the men than by their functioning as women?

Why, we ask, ever since men have been men, or rather since they became civilized — why have men in all times and places been irresistibly borne to make a differentiated division between the functions of the two sexes? Do we not have here strict testimony to the recognition by all mankind of a truth and a law above man?

To sum up, wherever women wear men’s dress, it is to be considered a factor in the long run tearing apart human order.

IV

The logical consequence of everything presented so far is that anyone in a position of responsibility should be possessed by a sense of alarm in the true and proper meaning of the word, a severe and decisive alarm.

We address a grave warning to parish priests, to all priests in general and to confessors in particular, to members of every kind of association, to all religious, to all nuns, especially to teaching Sisters.

We invite them to become clearly conscious of the problem so that action will follow. This consciousness is what matters. It will suggest the appropriate action in due time. But let it not counsel us to give way in the face of inevitable change, as though we are confronted by a natural evolution of mankind, and so on!

Men may come and men may go, because God has left plenty of room for the to and fro of their free-will; but the substantial lines of nature and the not less substantial lines of Eternal Law have never changed, are not changing and never will change. There are bounds beyond which one may stray as far as one sees fit, but to do so ends in death; there are limits which empty philosophical fantasizing may have one mock or not take seriously, but they put together an alliance of hard facts and nature to chastise anybody who steps over them. And history has sufficiently taught, with frightening proof from the life and death of nations, that the reply to all violators of the outline of “humanity” is always, sooner or later, catastrophe.

From the dialectic of Hegel onwards, we have had dinned in our ears what are nothing but fables, and by dint of hearing them so often, many people end up by getting used to them, if only passively. But the truth of the matter is that Nature and Truth, and the Law bound up in both, go their imperturbable way, and they cut to pieces the simpletons who upon no grounds whatsoever believe in radical and far-reaching changes in the very structure of man.

The consequences of such violations are not a new outline of man, but disorders, hurtful instability of all kinds, the frightening dryness of human souls, the shattering increase in the number of human castaways, driven long since out of people’s sight and mind to live out their decline in boredom, sadness and rejection. Aligned on the wrecking of the eternal norms are to be found the broken families, lives cut short before their time, hearths and homes gone cold, old people cast to one side, youngsters willfully degenerate and — at the end of the line — souls in despair and taking their own lives. All of which human wreckage gives witness to the fact that the “line of God” does not give way, nor does it admit of any adaption to the delirious dreams of the so-called philosophers!

V

We have said that those to whom the present Notification is addressed are invited to take serious alarm at the problem in hand. Accordingly they know what they have to say, starting with little girls on their mother’s knee.

They know that without exaggerating or turning into fanatics, they will need to strictly limit how far they tolerate women dressing like men, as a general rule.

They know they must never be so weak as to let anyone believe that they turn a blind eye to a custom which is slipping downhill and undermining the moral standing of all institutions.

They, the priests, know that the line they have to take in the confessional, while not holding women dressing like men to be automatically a grave fault, must be sharp and decisive.

Everybody will kindly give thought to the need for a united line of action, reinforced on every side by the cooperation of all men of good will and all enlightened minds, so as to create a true dam to hold back the flood.

Those of you responsible for souls in whatever capacity understand how useful it is to have for allies in this defensive campaign men of the arts, the media and the crafts. The position taken by fashion design houses, their brilliant designers and the clothing industry, is of crucial importance in this whole question. Artistic sense, refinement and good taste meeting together can find suitable but dignified solution as to the dress for women to wear when they must use a motorcycle or engage in this or that exercise or work. What matters is to preserve modesty together with the eternal sense of femininity, that femininity which more than anything else all children will continue to associate with the face of their mother.

We do not deny that modern life sets problems and makes requirements unknown to our grandparents. But we state that there are values more needing to be protected than fleeting experiences, and that for anybody of intelligence there are always good sense and good taste enough to find acceptable and dignified solutions to problems as they come up.

Out of charity we are fighting against the flattening out of mankind, against the attack upon those differences on which rests the complementarity of man and woman.

When we see a woman in trousers, we should think not so much of her as of all mankind, of what it will be when women will have masculinized themselves for good. Nobody stands to gain by helping to bring about a future age of vagueness, ambiguity, imperfection and, in a word, monstrosities.

This letter of Ours is not addressed to the public, but to those responsible for souls, for education, for Catholic associations. Let them do their duty, and let them not be sentries caught asleep at their post while evil crept in.

Giuseppe Cardinal Siri,

Archbishop of Genoa

From a Torah obedient perspective it is clear that believers in Messiah Yeshua shouldn’t be involved in modern cross-dressing or in any attempts to blur moral standards or the natural distinctions of creation. These standards and distinctions should instead be cherised and accentuated by cultural norms. Many of these norms are given and upheld by divine revelation. The Torah explicitly warns us against cross-dressing, which is considered an abomination in Dt. 22:5. The Body of Messiah has the clear and unambiguos obligation to uphold a biblical and traditional culture in matters of sexual morality.

_____________

[1] Giuseppe Cardinal Siri (1906-1989) was Archbishop of Genoa. His Notification can be found at: http://olrl.org/virtues/pants.shtml

[2] ‘Natural law’ can be defined as the collection of moral principles and norms detectible by natural reason unaided by divine revelation. The Apostle Paul refers to the natural law in Rom. 1:18-32.

In een recent rondschrijven van Wim Verdouw, voorganger van de Immanuel Gemeente (of Gemeente van het Levende Woord) te Alblasserdam, wordt de stelling betrokken dat het vasten op de Verzoendag (Jom Kippoer) geen verplichting is volgens de instructies in Leviticus hst. XXIII en dat dit vasten daarom niet opgelegd mag worden. Het lijkt mij dat in deze stellingname een aantal misverstanden schuilgaan.

In een recent rondschrijven van Wim Verdouw, voorganger van de Immanuel Gemeente (of Gemeente van het Levende Woord) te Alblasserdam, wordt de stelling betrokken dat het vasten op de Verzoendag (Jom Kippoer) geen verplichting is volgens de instructies in Leviticus hst. XXIII en dat dit vasten daarom niet opgelegd mag worden. Het lijkt mij dat in deze stellingname een aantal misverstanden schuilgaan.

Recent Comments